Fashion Unraveled

Fashion Unraveled was not your typical fashion exhibition. Rather than feature pristine clothes that

exemplify a theme, a time period, or a designer's aesthetic, it explored the roles

of memory and imperfection in fashion. The exhibition also highlighted the aberrant

beauty in flawed objects, giving precedence to garments that have been altered, left

unfinished, or deconstructed. These selections underscored one elemental fact about

clothing: that it is designed to be worn and has, in some cases, been worn out.

Traces of wear, shortened hemlines, and careful mends can be found even on haute couture

designs. These alterations signify the lasting economic and emotional value of clothing

and, in some cases, challenge the concept of fashion as a strictly ephemeral, disposable

commodity. Unless such imperfections are intentional — as they are in deconstructed

fashion — these garments are often overlooked within museum collections. If they are

selected for exhibition, curators rely on the expert work of a conservator, a gallery's

low lighting, or strategic placement to cleverly obscure flaws. In recent years, however,

as interest in the "biographies" of garments has grown, fashion historians have begun

to reassess imperfect objects. Studies of specific items may reveal intriguing histories

about their wearers and/or makers, poignant reminders of the deeply personal and physical

relationships we have with our clothes.

not your typical fashion exhibition

Wearing Memories

Fashion Unraveled Colloquium: Memory, Wear, and Imperfection in Dress

Worn in New York

In the Press

Behind The Seams

Clothing brought into The Museum at FIT collection sometimes arrives with tales about its maker, its wearer, or its historical significance. While these anecdotes are documented in the museum’s database, curators usually do not reference them when a garment is displayed. Such stories are not always evident in an object's appearance. A 1956 evening gown by Jean Desses is a stunning example of the couturier's work, but the information provided by its donor is also of note. The gown was gifted by Lady Arlene Kieta, one of Desses's models, who disclosed to the museum that it was made from 66 yards of chiffon fabric and cost $15,000 at the time of its creation.

Mended And Altered

The economic value of clothing often ensured its long-term maintenance, and many objects owned by MFIT show signs of mending and alterations. A set of stays from circa 1750 was enlarged by adding panels of mismatched fabric at the waist, reshaping it for a changed figure or a new wearer. An owner might have myriad reasons to modify a garment — to keep pace with newly fashionable silhouettes, for example, or for use as a theater costume. Others reconditioned their clothes for sentimental reasons. A Chanel suit worn by fashion photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe shows evidence of alterations and replacement components, revealing her ongoing affection for the ensemble.

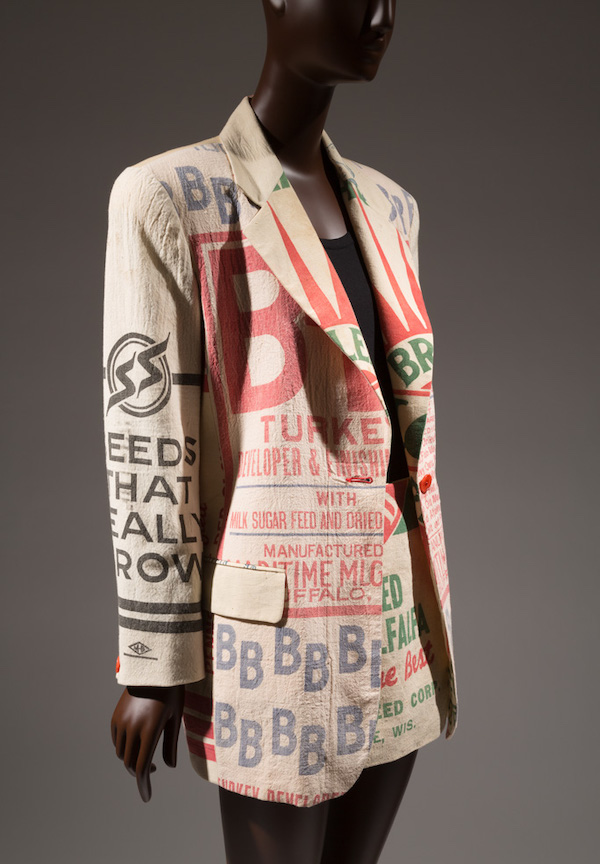

Repurposed

Repurposed garments are made from existing clothing or textiles into something new. Such designs highlight both the resourcefulness of their makers and the lasting value of the materials. Charles Frederick Worth, a couturier who was well known for using luxurious fabrics, fashioned a circa 1890 evening cape from eighteenth-century lace. A 1966 jumpsuit designed and worn by Betsey Johnson takes a more colorful approach: it was cleverly remade from rugby shirts worn by her then-partner, musician John Cale. By the 1990s, repurposing was often used to make a statement about overconsumption and obsolescence in fashion.

Unfinished

Unfinished garments initially may not seem worthy of inclusion in a museum collection, but they can provide fascinating insight into the processes of making fashion. An unknown dressmaker embellished a circa 1880 bustle gown with an unusual, raw-edged trim — but what is even more intriguing is that the dress was never finished. In several areas, the garment's trim was left basted on rather than properly stitched. Today an unfinished appearance, often in the form of frayed edges, is fashionable even among high-end designers. An Oscar de la Renta dress from 2002 is adorned with sequins, ostrich feathers, and an artfully unraveled hem.

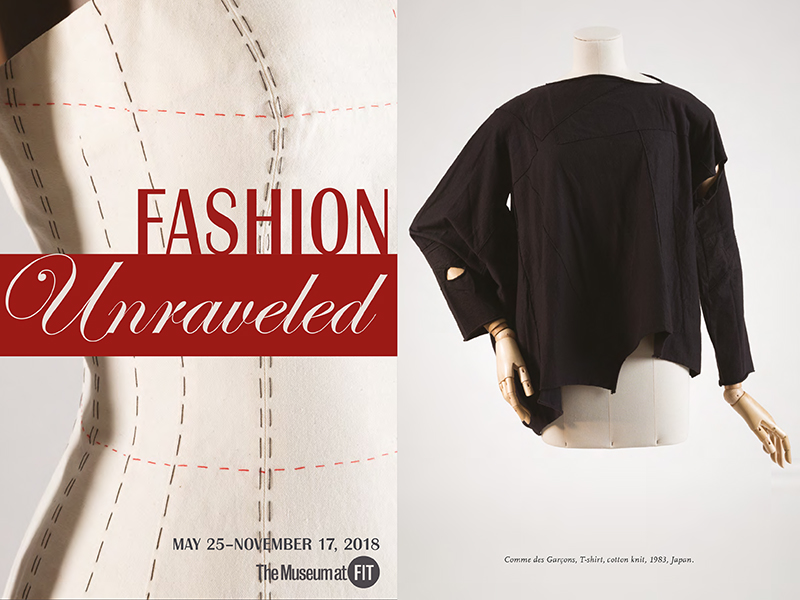

Distressed And Deconstructed

Distressed and deconstructed fashion has a deliberately worn or imperfect aesthetic — a concept that became increasingly important during the latter half of the twentieth century. Giorgio di Sant'Angelo fashioned garments from bleached, irregularly stitched panels of suede during the late 1960s. By the early 1980s, Rei Kawakubo's work for her label Comme des Garcons took those ideas to a new extreme: a black knit T-shirt was intentionally faded, and its asymmetrical pieces were haphazardly assembled, leaving gaps and unfinished edges. Martin Margiela's spring 1990 "tabi" boots were heavily varnished with thick white paint. He intended the boots to continually crack and deteriorate over time — calling attention to fashion’s ephemerality.

Comme des Garçons T-shirt, cotton knit, 1983, Japan, gift of Ms. Terry Melville, 90.98.69

Maison Martin Margiela boots, painted canvas, spring 1990, Belgium, gift of Richard Martin, 92.182.1

Vivienne Westwood jacket, rayon satin, spring 1991, England, museum purchase, 98.140.1

Fashion Unraveled was organized by Colleen Hill, curator of costume and accessories at The Museum at

FIT.

Fashion Unraveled was supported by the Couture Council.

![]()